The Trojan Women

Euripides (trans. Nicholas Rudall)

University of Idaho

Kiva Theatre

2003

Production team:

Scenic Design: Karla Rose

Costume Design – Carrie Loudy & Liz Burks

Asst. Costume Designer – Masako Hojo

Make Up Design – Shasta Hankins

Puppet Design – Angela Bengford

Lighting Design – Brett Affleck-Aring

Asst. Lighting Designer – Sheri Intermill

Sound Design – Rob Kreps

- The Trojan Women & Poseidon

- The Greeks, Astyanax, & Hecuba

- Hecuba & the Women

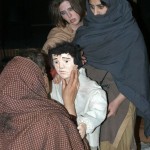

- Women w/ Astyanax

- Hecuba & Astyanax

- The Trojan Women

The Trojan Women is an anti-war play. It is also a play about women, a play about human relationships, a play about loyalty, and a play about classical mythology. However, at its core, it is a play about the perils and tragic foolishness of waging war. In his introduction to the play, translator Nicholas Rudall explains that the play was first performed in Athens in 415 B.C. In 416 B.C., Athens invaded the neutral Greek island of Melos. Athenian troops had enslaved the island’s women and children after killing off the men. Euripides’s native audience would have seen his play as an obvious critique on the invasion that took place only one year earlier (3). The Trojan Women criticized its society publicly from the vantage point of the Theatre of Dionysus. Cassandra says early in the play, “In the end it comes to this: a wise man will never go to war.” This is the paramount theme of the play. Poseidon tells us in his prologue, “The man who sacks cities and desecrates temples and the holy tombs of the dead is mad. His own doom is merely…waiting” (14). Euripides structures the play around this simple notion: “War is foolish.” This truth coupled with the historical context of the piece makes it very difficult, if not irresponsible, to direct this play today without allowing our own nation’s current military involvement, “The War on Terror,” to influence how this production takes shape. In the end, war solves very little. Euripides knew this, and his play may now serve the same function in A.D. 2004 that it served in 415 B.C.

I am an idealist, but I am not so naïve as to think the world will be changed because of one play. The theatre is the most politically powerful of any artistic medium. Still, nothing was markedly changed after the original performance of The Trojan Women some 2,400 years ago. With that said, I do view this play as a potential catalyst for debate. In the months after September 11, 2001, one dared not argue or even question our government. Now, where will this new war end? The questions go on, but few people dare to discuss them. At the very least, this production has the potential to spark that discussion within our community.

To achieve this, the design team and I must underscore the parallels between the ancient Greeks and our modern culture. However, there is a fine line between clarity of the metaphor and browbeating the audience. The audience will arrive at the theatre already saturated with news of our current crisis. All we have to do is provide hints and flavors, and they will make the natural connection. The costumes must suggest modernity without designating individual cultures. The Greek guards’ costuming should suggest Western military without stitching a flag on their shoulders; the Trojan women’s attire should display influences from the various cultures invaded by the west without pointing at specific nations. The effect will be that the Trojan women are part of an ambiguous foreign culture while the Greeks represent that which is familiar to the audience. To be clear, I do not want to overtly depict an American versus Iraqi situation. This would limit the play immensely. The conflict with Iraq is but one of many American conflicts. We should focus on placing subtle clarifying emphasis on the parallels between our nation’s military crises and the crisis between Ancient Greece and Troy. We merely have to hint.

The theatrical tradition of the ancient Greeks is captivating. Greek theatre seems virtually uncorrupted by commercialism. Theatre was not merely entertainment. Rather, it was completely fused within their society. It was a vital part of their cultural and religious rituals, and as such, The Trojan Women is one of the most unabashedly ritualistic pieces to come out of the ancient Greek tradition. The play overflows with songs, chants, organized ululations, prayers, and dirges. Again, in his translator’s note, Nicholas Rudall states, “Within the conventions of Greek drama, singing or chanting intensified the emotional impact…The Trojan Women contains proportionately more singing than any other Greek tragedy” (4). Euripides uses ritual as a medium for his message of peace.

In directing this play, I want to maintain this inherent sense of ritual, which is the author’s original intent. I am continually inspired by Anne Bogart’s book A Director Prepares. She writes, “As theatre artists, our job is to set up the circumstances in which an experience might occur” (69). With this production, I want to set up the circumstances for an event of shared ritual. As a director, I strive to regain elements of theatre’s ritualistic heritage. I want to create performances that continue to resonate with audiences long after the curtain call ends, and I am passionate about the power theatre has to transform audiences. When people are included and implicated in the world of the play, they are not as likely to dismiss the performance as mere entertainment.

Webster’s New World Dictionary defines “ritual” as: “A set form or system of rites, religious or otherwise” (1258). Ritual is a formalized process. Despite the ethereal connotations, ritual can be analytically broken down to its essential elements for use in the modern theatre. Objectifying the elements of ritual does not reduce the effect of the experience from the audience’s perspective; ritual is a powerful all-encompassing, sensual, and emotional experience. This has become something of an obsession for me. Whenever I witness ritual, whether as a participant or as an observer, I cannot help but analyze the occasion. In doing this, I have found that the basic tenants of ritual include atmospheric aroma or incense, stylized movement, repetition, music, and intimate spaces. While many cultures use these elements each with varying degrees of importance, these essential elements are cross-cultural. They can each be found in Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, and countless other religious rites. This provides modern theatre artists with a list of clear sign systems from which to work, and their cultural universality encourages their practical use in today’s theatre.

One of the most fascinating of ritual’s basic elements is the use of aroma. Infusing the theatre with carefully selected fragrances can clearly influence the audience’s response to the performance. The use of frankincense and myrrh during The Trojan Women will undoubtedly help create a reverent atmosphere in the theatre appropriate to ritual. The process of sanctification begins the moment the audience and actors sense the aroma upon entering the space. Given the historical and widespread ritualistic use of these resins, the audience will easily translate the use of incense as an act of ritual.

The use of aroma in the theatre is by no means a new concept. In her journal article titled “Olfactory Performances,” published in spring 2001 issue of The Drama Review, Sally Banes writes, “The deodorization of the modern theatre may also be one facet of a conscious move away from religious ritual” (68). She further blames the sterilizing, hygiene campaigns of the late 1800’s and early 1900’s for the reduced use of aroma as a legitimate sign system in the theatre; odors were increasingly linked with the proliferation of disease. For whatever reason, semioticians of the theatre continue to overlook the impact that odor can have on a performance. Kowzan, one of the most influential semioticians of the theatre, includes only auditive and visual signs in his table of classification. Odor seems like an obvious omission. How much would the smell of burning flesh affect the overall meaning during comedies like Neil Simon’s Lost in Yonkers? This is an extreme example, but suddenly, Kowzan’s classification seems overtly incomplete. Like Peter Brook’s use of incense in the 1985 production of The Mahabharata, incense in The Trojan Women will immediately begin building a sacred atmosphere in the theatre.

Along with aroma, the use of stylized movement is essential to create a sense of ritual in the theatre. Whether it is choreographed or free form, subtle or overt, rituals feature some sort of stylized movement. Early on, while working on the script, I began thinking of this play as having a structure similar to a modern stage musical. The play moves freely between chants, dialogue, and movement interludes in much the same way that a musical transitions between songs, dialogue, and dance breaks. Looking at The Trojan Women in this way allows me much more creative freedom. While structurally it will remain important to build to certain plot points, I am not locked into trying to force the play to flow linearly like modern realism.

The world of the play has its own rules, its own culture. I am fascinated by theatrical productions wherein the director and the actors create a distinct style of movement specific only to that world. This is what I am aiming for with this show. There are clear points in Euripides’s script that seem to be set aside for stylized, ritualistic movement. For example, there are moments during long elegies where I will use the four-member chorus to create brief emotionally charged movement sequences to punctuate the dialogue. While these interludes will feature both abstract and mimetic physicalizations of the characters’ emotions, I do not want the movements to be immediately representative of modern dance or mime. Again, these characters should move in a manner specific to their “culture.” I will emphasize expressionistic movement over concrete gesture. The emotional quality of the actors’ movements and the further development of ritual are the central focus of these sections.

The play will open with movement set to music that will tell the story of the Trojan War. The play itself begins at the conclusion of the war and presupposes that audience will have significant knowledge of the war. That was an easy assumption in 415 B.C., but today it is necessary to help the audience. The opening piece will serve as a prologue. It also extends the atmosphere of ritual. The trick will be to tell the story of Troy’s demise through movement alone. Before the actors and I can begin working to build the opener, we must thoroughly research the circumstances and history surrounding the Trojan War. Clearly, we are not going to be able to tell the entire story, but it is essential that we have a strong knowledge base from which to work. The opening piece should provide general historical information and set the emotional tone of the play. I am more interested that the audience witnesses a war in the first moments of the performance than I am that they witness the Trojan War specifically. I plan to work with improvisation and free form expressive movements around a central, general historical outline, Greeks versus Trojans. The play will be set in a place of worship, which is desecrated during the war. Poseidon tells us this in the first minute of the play. “Now the sacred places of the gods are silent, the temple walls weep blood…all respect has died” (11). When the audience enters the theatre, the set should appear untouched, sacred. Through the opening movement, the actors will tear the set apart, creating the necessary war torn, despoiled image. The audience will in essence witness the destruction of Troy through the guise of expressive ritualistic movement.

Whether in the form of a mantra, a prewritten mass, or a statement of creed, repetition is at the heart of ritual’s formalized process. Clearly, some productions lend themselves more easily to this than others. For example, in my production of Ionesco’s The Lesson, I edited the script to create a sense of formalized repetition in both movement and dialogue. The audience may not have left pondering the ritual, but the repetition created a ritualistic atmosphere that made the performance unique. The Trojan Women was written with this treatment in mind. Euripides uses repetition throughout the play. Often characters repeat a phrase several times in the course of a monologue. The effect is a formal poetic texture. Along with this textual repetition, much of the movement established in the opening movement piece will be repeated through the course of the play to bring the audience’s attention back to the war.

Following repetition, music is arguably the most universal aspect of ritual. It is hard to imagine a ritual without some form of musical expression. In this production of The Trojan Women, I plan to work closely with my sound designer to create a soundtrack for the piece that will help promote and maintain the sense of ritual. As part of my research, I have been listening to a wide variety of music in search of the right sound. Some examples that fit my concept include Dead Can Dance, Lisa Gerrard, and Jimi Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner.” The first two have the classic sound of ritual. They feature chant, organ tones, drums, and a sense of raw emotion. Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” fits well into my political concept, and the gritty harmonics and strange, erratic nature of the piece meld nicely with the emotional atmosphere of the play. The recorded music will be used to underscore moments such as the opening movement. In addition, the script calls for much of the dialogue, particularly the choral sections, to be chanted or sung. However, I want to be careful not to overuse chant in the play as it can begin to drone. I plan to add bits of it throughout, highlighting key moments. For example, as the Greeks carry the body of Astyanax away, the chorus will chant his funeral dirge. I want to reserve chant as a way to emphasize moments of distinct emotional peaks. I do not aim for the actors to sing these sections beautifully. The resulting sound may be atonal and dissonant; I am more interested in the emotional quality of the sound than I am the musicality.

Once the ritualistic elements of aroma, movement, music, and repetition are in place, it is important to discuss the location. Rituals typically take place in intimate spaces, set aside for the occasion: temples, churches, mosques, threshing circles, or dancing grounds. The space must fit the ritual. For this play, the proximity of the audience to the performers must be very intimate. For this to be a shared ritual, there cannot be barriers between the two. This production will take place in the Kiva Theatre on the UI campus. While this is the space assigned to the production, it is also the theatre I would have chosen. The intimate arena space forces the audience to sit very near the action. For this production, we will set up the seating into an avenue configuration. This accomplishes two things. First, on a practical level, in order to facilitate 14 actors moving freely through the space, the playing area must be extended past the central circle of the stage. It just gives the performance more space. Second, it provides for a more communal atmosphere with each half of the audience able to see the other. This should work against the established theatrical convention of a clear separation between audience and performers. The characters are free to interact with the audience. At times they will speak to them. At times they will not. At some points, the actors themselves will be speaking to the audience. This communal seating arrangement allows the audience to be a part of the experience rather than mere observers. The audience should feel like participants. They are a part of the world, part of the ritual.

The Trojan Women is an extremely complex politically motivated play. Written over 2,000 years ago, the play remains applicable today, but it lacks much of the major dramatic action of its modern counterparts. While this poses many challenges, it also opens the doors for creative freedom. This production will not be a typical passive experience for the audience. Instead, I hope to create what Euripides intended, a ritual for peace. In the final moment of the play, the chorus chants, “My city is no more. But we will walk on. We will walk on” (61). While the play mourns the atrocities of war, it leaves the audience with a statement of perseverance, of hope.

Sources:- Banes, Sally. “Olfactory Performances.” The Drama Review. 45, 1 (T169), Spring 2001: 68-76.

- Bogart, Anne. A Director Prepares. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Euripides. The Trojan Women. Trans. Nicholas Rudall. Chicago. Ivan R. Dee, 1999.

- Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language. College Edition. Cleveland: The World Publishing Co., 1964.